OAuth 2.0

OAuth 2.0 Terminology

- Resource Owner: Entity that can grant access to a protected resource. Typically, this is the end-user.

- Client: Application requesting access to a protected resource on behalf of the Resource Owner.

- Resource Server: Server hosting the protected resources. This is the API you want to access.

- Authorization Server: Server that authenticates the Resource Owner and issues Access Tokens after getting proper authorization. In this case, Auth0.

- User Agent: Agent used by the Resource Owner to interact with the Client (for example, a browser or a native application).

Applications in Auth0

Application type: To add authentication to your application, you must register it in the Auth0 Dashboard and select from one of the following application types:

- Regular web application: Traditional web apps that perform most of their application logic on the server (such as Express.js or Django). To learn how to set up a regular web application, read Register Regular Web Applications.

- Single page web application (SPA): JavaScript apps that perform most of their user interface logic in a web browser, communicating with a web server primarily using APIs (such as AngularJS + Node.js or React). To learn how to set up a Single-page web application, read Register Single-Page Web Applications.

- Native application: Mobile or Desktop applications that run natively on a device (such as iOS or Android). To learn how to set up a native application, read Register Native Applications.

- Machine to machine (M2M) application: Non-interactive applications, such as command-line tools, daemons, IoT devices, or services running on your backend. Typically, you use this option if you have a service that requires access to an API. To learn how to set up a native application, read Register Machine-to-Machine Applications.

Token Type

There are two types of tokens that are related to identity: ID tokens and access tokens.

ID tokens

ID tokens are JSON web tokens (JWTs) meant for use by the application only. For example, if there's an app that uses Google to log in users and to sync their calendars, Google sends an ID token to the app that includes information about the user. The app then parses the token's contents and uses the information (including details like name and profile picture) to customize the user experience.

Do not use ID tokens to gain access to an API. Each token contains information for the intended audience (which is usually the recipient). According to the OpenID Connect specification, the audience of the ID token (indicated by the aud claim) must be the client ID of the application making the authentication request. If this is not the case, you should not trust the token.

{

"iss": "http://YOUR_DOMAIN/",

"sub": "auth0|123456",

"aud": "YOUR_CLIENT_ID",

"exp": 1311281970,

"iat": 1311280970,

"name": "Jane Doe",

"given_name": "Jane",

"family_name": "Doe",

"gender": "female",

"birthdate": "0000-10-31",

"email": "janedoe@example.com",

"picture": "http://example.com/janedoe/me.jpg"

}

This token authenticates the user to the application. The audience (the aud claim) of the token is set to the application's identifier, which means that only this specific application should consume this token.

Conversely, an API expects a token with the aud value to equal the API's unique identifier. Therefore, unless you maintain control over both the application and the API, sending an ID token to an API will generally not work. Since the ID token is not signed by the API, the API would have no way of knowing if the application had modified the token (e.g., adding more scopes) if it were to accept the ID Token. See the JWT Handbook for more information.

Access tokens

Access tokens (which aren't always JWTs) are used to inform an API that the bearer of the token has been authorized to access the API and perform a predetermined set of actions (specified by the scopes granted).

In the Google example above, Google sends an access token to the app after the user logs in and provides consent for the app to read or write to their Google Calendar. Whenever the app wants to write to Google Calendar, it sends a request to the Google Calendar API, including the access token in the HTTP Authorization header.

Access tokens must never be used for authentication. Access tokens cannot tell if the user has authenticated. The only user information the access token possesses is the user ID, located in the sub claim. In your applications, treat access tokens as opaque strings since they are meant for APIs. Your application should not attempt to decode them or expect to receive tokens in a particular format.

{

"iss": "https://YOUR_DOMAIN/",

"sub": "auth0|123456",

"aud": ["my-api-identifier", "https://YOUR_DOMAIN/userinfo"],

"azp": "YOUR_CLIENT_ID",

"exp": 1489179954,

"iat": 1489143954,

"scope": "openid profile email address phone read:appointments"

}

Note that the token does not contain any information about the user besides their ID (sub claim). It only contains authorization information about which actions the application is allowed to perform at the API (scope claim). This is what makes it useful for securing an API, but not for authenticating a user.

In many cases, you might find it useful to retrieve additional user information at the API, so the access token is also valid for calling the /userinfo endpoint, which returns the user's profile information. The intended audience (indicated by the aud claim) for this token is both your custom API as specified by its identifier (such as https://my-api-identifier) and the /userinfo endpoint (such as https://YOUR_DOMAIN/userinfo).

Token Best Practices

Here are some basic considerations to keep in mind when using tokens:

- Keep it secret. Keep it safe: The signing key should be treated like any other credential and revealed only to services that need it.

- Do not add sensitive data to the payload: Tokens are signed to protect against manipulation and are easily decoded. Add the bare minimum number of claims to the payload for best performance and security.

- Give tokens an expiration: Technically, once a token is signed, it is valid forever—unless the signing key is changed or expiration explicitly set. This could pose potential issues so have a strategy for expiring and/or revoking tokens.

- Embrace HTTPS: Do not send tokens over non-HTTPS connections as those requests can be intercepted and tokens compromised.

- Consider all of your authorization use cases: Adding a secondary token verification system that ensures tokens were generated from your server may be necessary to meet your requirements.

- Store and reuse: Reduce unnecessary roundtrips that extend your application's attack surface, and optimize plan token limits (where applicable) by storing access tokens obtained from the authorization server. Rather than requesting a new token, use the stored token during future calls until it expires. How you store tokens will depend on the characteristics of your application: typical solutions include databases (for apps that need to perform API calls regardless of the presence of a session) and HTTP sessions (for apps that have an activity window limited to an interactive session). For an example of server-side storage and token reuse, see Token Storage.

Authorization Flows

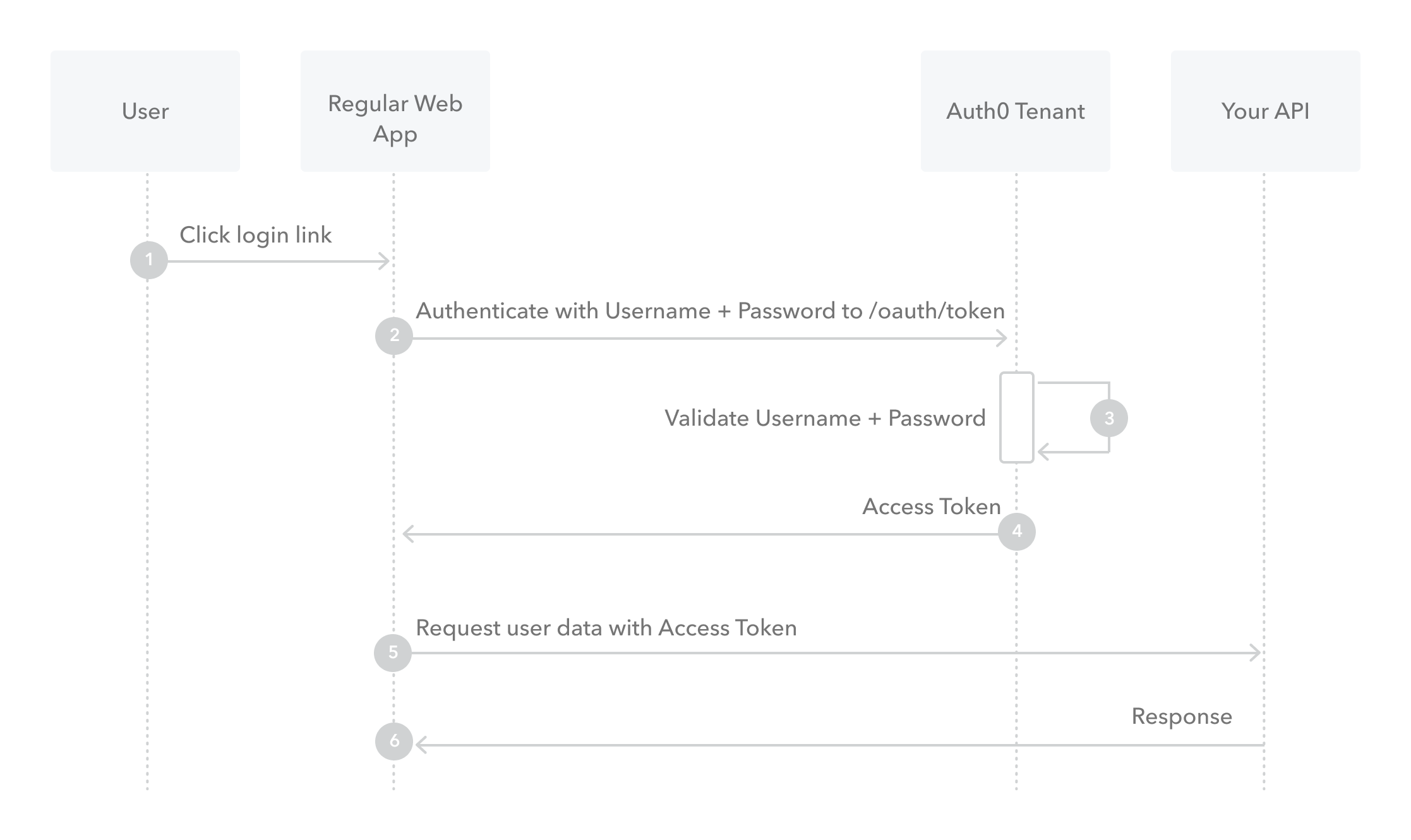

Resource Owner Password Flow

Though we do not recommend it, highly-trusted applications can use the Resource Owner Password Flow (defined in OAuth 2.0 RFC 6749, section 4.3), which requests that users provide credentials (username and password), typically using an interactive form. Because credentials are sent to the backend and can be stored for future use before being exchanged for an Access Token, it is imperative that the application is absolutely trusted with this information.

Even if this condition is met, the Resource Owner Password Flow should only be used when redirect-based flows (like the Authorization Code Flow) cannot be used.

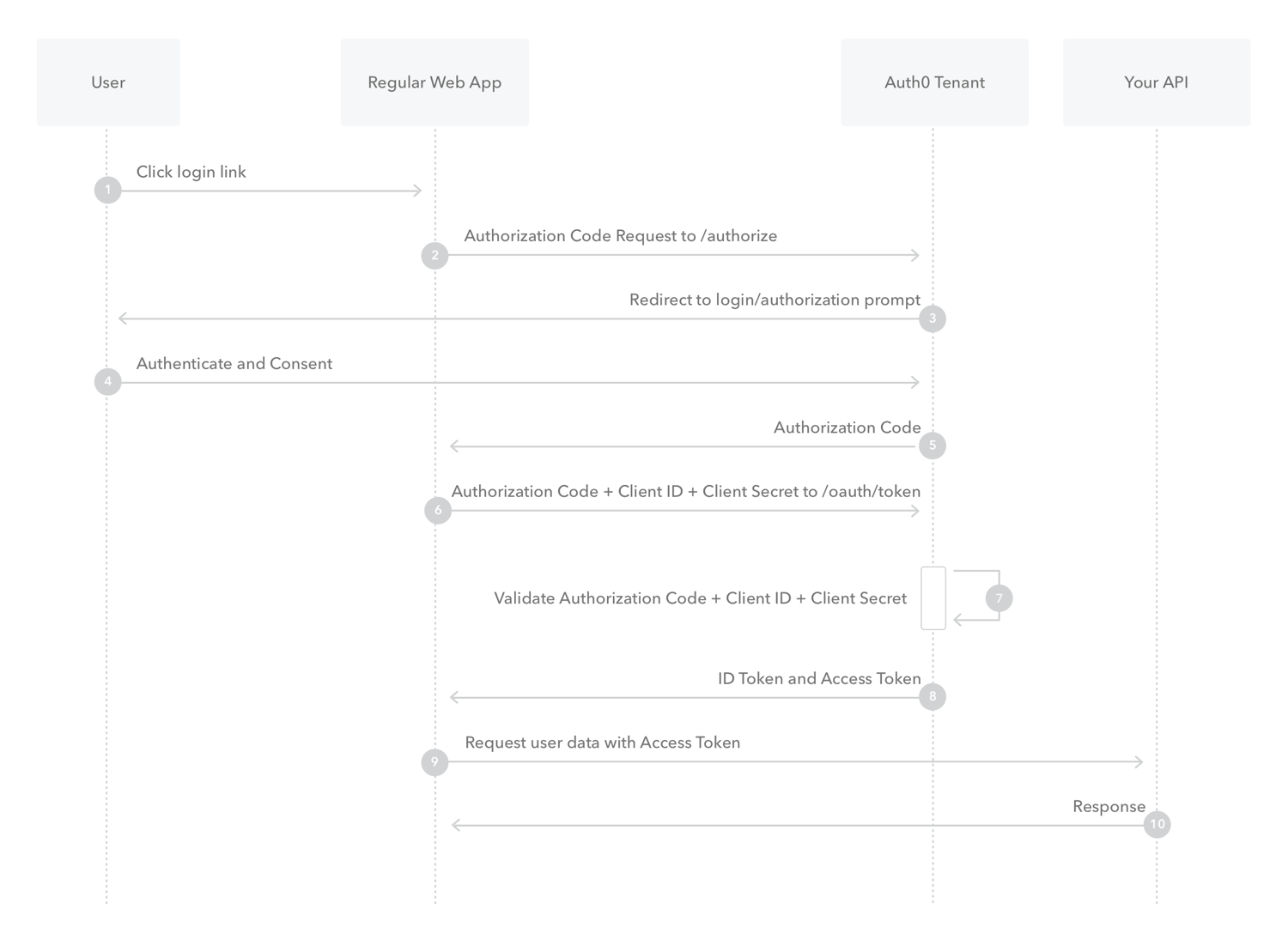

Authorization Code Flow

Because regular web apps are server-side apps where the source code is not publicly exposed, they can use the Authorization Code Flow (defined in OAuth 2.0 RFC 6749, section 4.1), which exchanges an Authorization Code for a token. Your app must be server-side because during this exchange, you must also pass along your application's Client Secret, which must always be kept secure, and you will have to store it in your client.

Implicit ID Token Flow

You can use OpenID Connect (OIDC) with many different flows to achieve web sign-in for a traditional web app. In one common flow, you obtain an ID token using authorization code flow performed by the app backend. This method is effective and robust, however, it requires your web app to obtain and manage a secret. You can avoid that burden if all you want to do is implement sign-in and you don’t need to obtain access tokens for invoking APIs.

Implicit Flow with Form Post flow uses OIDC to implement web sign-in that is very similar to the way SAML and WS-Federation operates. The web app requests and obtains tokens through the front channel, without the need for secrets or extra backend calls. With this method, you don’t need to obtain, maintain, use, and protect a secret in your application.

Implicit response_type=id_token flow is perfect for simply authenticating your end-users, assuming the only job you want done is authenticating the user and then relying on your own session mechanism with no need for accessing any third party APIs with an Access Token from the Authorization Server.

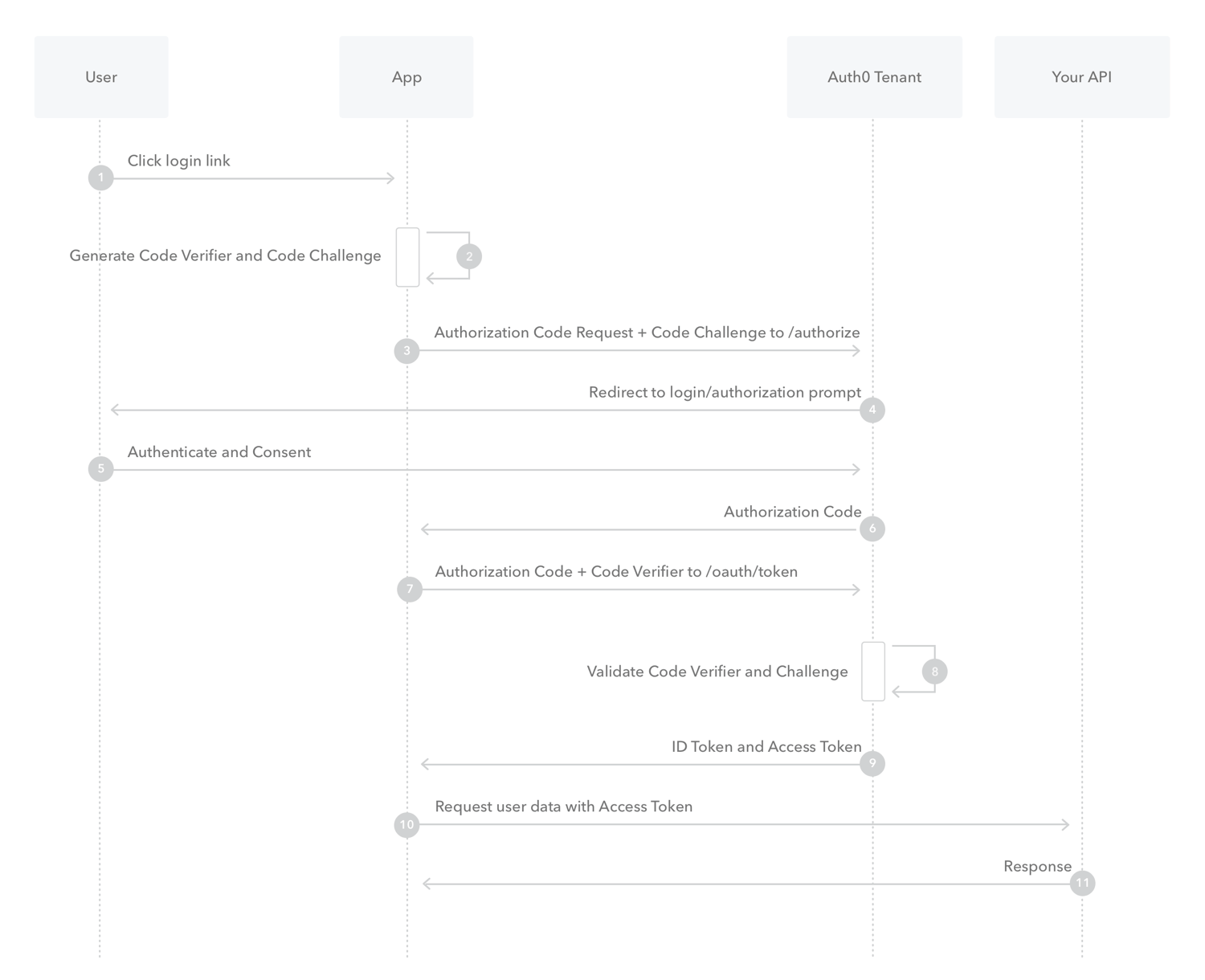

Authorization Code Flow with Proof Key for Code Exchange (PKCE)

When public clients (e.g., native and single-page applications) request Access Tokens, some additional security concerns are posed that are not mitigated by the Authorization Code Flow alone. This is because:

Native apps

- Cannot securely store a Client Secret. Decompiling the app will reveal the Client Secret, which is bound to the app and is the same for all users and devices.

- May make use of a custom URL scheme to capture redirects (e.g., MyApp://) potentially allowing malicious applications to receive an Authorization Code from your Authorization Server.

Single-page apps

- Cannot securely store a Client Secret because their entire source is available to the browser.